“What to expect when a giant cloud of gas collides with your galaxy?”

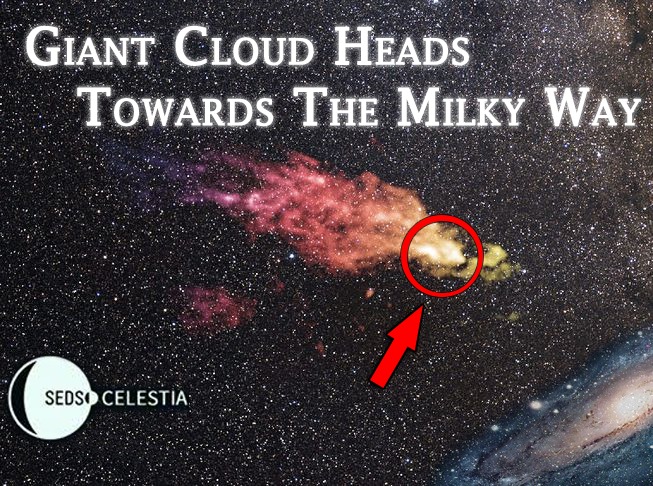

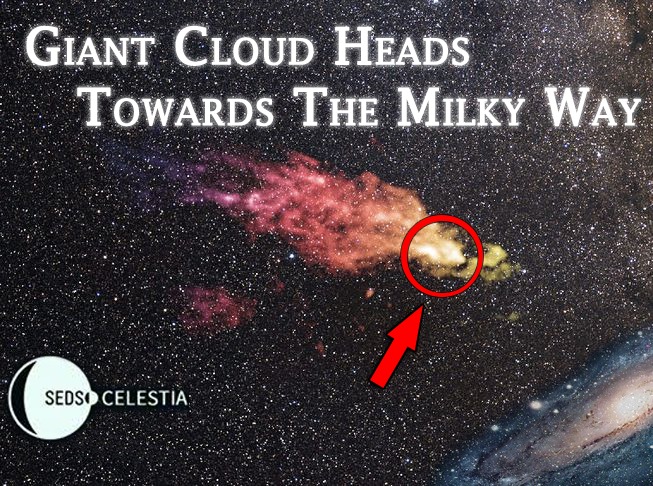

When scientists were working to discover more about the universe and especially our own galaxy in the early 1960s, one of the few celestial discoveries of the time included the Smith’s Cloud. In 1963, when discovered by doctoral astronomer Gail Smith, it was believed to be just an extension of the Milky Way, and nothing was known about its motion. It was only decades later that Astronomer could make a detailed image of it and calculate its velocity and exact composition. Smith’s Cloud is a large, high-velocity hydrogen gas cloud in the constellation of Aquila. It is 11,000 light years long and 2,500 light years wide. It is about 8,000 light years away from our galaxy’s plane at an angle of about 45 degrees. However, the initial assumption that Smith’s Cloud is an extension of the Milky Way was proven wrong when it was discovered that it is heading for a collision with the Milky Way at a velocity of more than 240 km/s and is already interacting with the gases at the edges of the galaxy.

Ever since its independent nature was discovered, astronomers theorized that Smith’s Cloud is merely an interstellar cloud which travelled across space and was caught in the gravitational pull of the Milky Way. This would have been true if Smith’s Cloud was composed of only hydrogen and helium. In order to determine the exact origins of the Cloud, astronomers decided to calculate the Cloud’s exact chemical composition. Using three galaxies which are billions of light years away and lie in the same direction from earth as Smith’s Cloud as the source of ultraviolet light, astronomers used the Hubble Telescope’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph to measure the amount of ultraviolet light that the Cloud absorbs. From the spectrum of ultraviolet light obtained, the amount of sulpher present was calculated, since the amount of sulpher allows scientists to estimate the amount of other, heavier elements using the sun’s composition as a reference. The most interesting part is that the percentage of sulpher in Smith’s Cloud matches that in the outer disk of the Milky Way. Thus, it is proven that Smith’s Cloud was formed of materials ejected from the Milky Way and is now falling back into the galaxy. If Smith’s Cloud has formed of materials from our galaxy, it could mean that often such clouds are formed from galaxies which then return to the galaxy, crashing back onto another part of the galaxy.

In such a manner, a lot of galaxies could “recycle” such clouds of unused gases. Furthermore, the fact that this cloud of gas is heading back towards the galaxy has caused great excitement in the scientific community since it could mean a new chain of star formation. In 2007, astronomers Felix J. Lockman, Robert A. Benjamin, A. J. Heroux, Travis Fischer and Glen I. Langston presented to the 211th meeting of the American Astronomical Society their results from detailed observations of Smith’s Cloud using the Green Bank Telescope. Their findings concluded that Smith’s Cloud is heading towards the plane of the galaxy and would crash into the Perseus arm of Milky Way in about 30 million years. This can trigger a wave of star formation, with massive stars being formed which would rush through their lives quickly and explode as supernovae. This discovery further supports the hypothesis of gas recycling by galaxies, allowing such unused gases to form more stars. On the whole, the trajectory of Smith’s Cloud has provided an insight into the life cycle of galaxies and their interaction with interstellar matter. Moreover, detailed data from the Green Bank Telescope allowed astronomers to follow the trajectory of Smith’s Cloud backwards in time. According to simulations, about 70 million years ago Smith’s Cloud passed through the plane of the galaxy with little or no loss of matter. Also, research papers submitted in 2009 conclude that Smith’s Cloud may be a hundred times more massive than earlier estimates, putting its mass at around 300 million solar masses. A gas cloud that massive cannot survive a collision with the Milky Way and should disintegrate on collision.

Despite that, Smith’s Cloud seems to have survived such a huge collision in the past and is again headed for another collision (though researchers believe that Smith’s Cloud may not survive this collision; tidal forces have already begun to tear it apart). The fact that Smith’s Cloud survived such a collision led astronomers to theorize that Smith’s Cloud is encapsulated in a dark-matter “halo”, which protected the Cloud from the destructive tidal forces and led it to its current trajectory. This theory, if proven, could explain how the earliest stars in our galaxy were formed. Furthermore, this theory also leads to the possibility that Smith’s Cloud, in fact, is a failed, dwarf galaxy which may have been formed from the gases left over from the initial wave of star formation in the Milky Way, and would allow astronomers to estimate a lower limit on the size of galaxies in general. On the whole, Smith’s Cloud is one of the most unique objects in the night sky which, due to its closeness to us allows us to study it in great detail, and provides us with an insight into the history of the Milky Way and how our galaxy, and in general most galaxies, operates. Further research into this unique phenomenon will provide us with more knowledge of our universe.